STORY PARADE: THE CAVES OF STEEL - PRESS COVERAGE

[The Radio Times 28/05/64]

Isaac

Asimov's outstanding science-fiction novel

Isaac

Asimov's outstanding science-fiction novel

dramatised for Story Parade

starring Peter Cushing

THE CAVES

OF STEEL

NEW YORK some 200 years from now: a city of 14-million people living in one

vast domed hall, looking on the open countryside as dangerous territory.

Beyond is Spacetown, where the scientists from other worlds who have

subjugated Earth study the human species in the hope of saving it from

self-extinction. When one of their scientists is found murdered, the

'Spacers' issue an ultimatum. Unless the killer is found within forty-eight

hours, New York may be destroyed. The city's Deputy Commissioner of

Police, Elijah Baley, has the task of solving the case, with the aid of a

detective from Spacetown named R. Daneel Olivaw. The 'R' stands for

Robot...

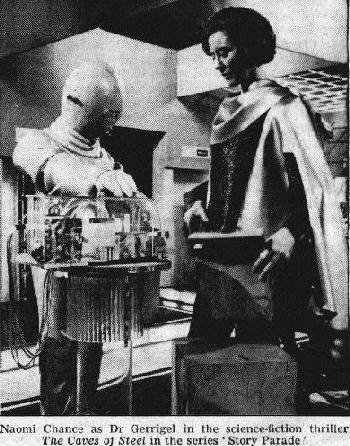

Dramatised by Terry Nation from the novel by Isaac Asimov,

The Caves of Steel is science fiction at its most intriguing.

Directed by Peter Sasdy, the play stars Peter Cushing as Elijah

Baley. Several times winner of television 'best actor' awards, he is

thoroughly at home in the realm of fantasy, having starred in such films

as The Flesh and the Fiend, The Mummy, and The Evil of

Frankenstein.

Commissioner Enderby is played by Kenneth J. Warren, who appeared

recently in the comedy thriller Justin Thyme; while John Carson, whom

many viewers will have seen earlier this year in Murder in the

Cathedral, has the part of R. Daneel Olivaw.

[The Times 13/06/64]

NOTES ON BROADCASTING

In the Hands of the Adaptor

FROM OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT

Pity the poor adaptor. Most of the time no one takes any notice of him, and on the rare occasions that they do as often as not they leave him wishing they had not. For the tiresome truth is that the only time people really notice an adaptation is when it leaves something to be desired: if it works they give the credit to the original; if it fails they blame the adaptor. A new series on B.B.C.2, "Story Parade", raises such questions in a fairly acute manner, since each week it presents a dramatized version, running as a rule about 75 minutes, of a novel written in the past 30 years. That is all: no type of novel specified, no level of brow particularly in mind (actually, a little more definition in these regions would probably be a good thing), and apparently the principle criterion for inclusion in the series reasonably straightforward adaptability within a, one would guess, fairly modest budget.

NO EASY TASK

It sounds easy. Just walk into a library, one might think, pick up an armful of books off the shelves, and there you are set up for the season. But by looking at the series, which has now been running for eight weeks, one can soon tell that, quite apart from any question of what rights are and are not available, it is not at all as simple as that. Unfairly, of course, it is only when things go pretty obviously wrong that the technical side of the business obtrudes itself on the ordinary viewer's consciousness: Stanley Miller's adaptation of Max Frisch's novel I'm Not Stiller under the title Condemned to Acquittal, which opened the series, went off without a hitch, and so Mr. Frisch received the plaudits and Mr. Miller's part in seizing the essential of quite a difficult novel and presenting it economically in dramatic terms was largely ignored. Again, in a very different register, Terry Nation's adaptation of Ira Levin's thriller A Kiss Before Dying, a much easier job to begin with, since the original novel seems to have been written with half an eye on the cinema screen, turned out to be a highly polished, holding piece of light entertainment, and the work which went into making it just that was taken for granted.

With other productions in the series, though, we become more conscious of the problems. As it happens, various adaptor's difficulties can be illustrated rather neatly from them, one play to each difficulty. First, there is the question of understanding the syntax of the novel, the way it is put together in order to work, and reconstructing it in a different medium. Leon Griffith's adaptation of Eric Linklater's Mr. Byculla ran into complication here. If you have read the book you know right away that Byculla is a thug – literally speaking, that is; he practices thuggee in modern England. But for those who had not read the book – the majority, obviously, of the viewing public – Mr. Griffiths omitted to make this clear in anything but obscure hints, and consequently what exactly this mysterious but apparently well-meaning Indian gentleman was up to must have remained impenetrably obscure to most viewers of the play – if they waited so long. Terry Nation's otherwise highly successful version of Isaac Asimov's science-fiction story The Caves of Steel ran into a variation of this difficulty: the story hinges on a fanatical hatred of robots by most people in a remote future. Why do they hate them? We are supposed, apparently, to link up immediately with race hatred in the modern world, but that, though it may work in a novel or short story, just will not do so in a play. In a play we want to know more of the whys and hows: are the robots putting humans out of their jobs? (it seems not); are they likely to rebel? (they are physically unable to); are they seducing the humans' wives? (perish the thought!). We are not told, and so a vital link in the chain of satisfactory drama is missing.

Charles Cohen's version of Gerard Bessett's Not for Every Eye and Alun Richard's version of his own The Elephant You Gave Me bring in two more, probably more common, complications. The Bessette novel is about unofficial Church censorship of books in provincial Canada, which, whatever its implied message about freedom of speech and all that is just a tiny bit remote for British viewers, especially considering that the books concerned are Voltaire and Gide (the works of the latter, incidentally, are at one point knowingly asked for by a strapping woodsman: though one knows about the culture of the French and all that, this does seem a little hard to swallow). Closer to home, Alun Richards stumbled over something which is a more basic matter of adapting technique: given a novel which has two interwoven plots of almost equal importance, what does the adaptor do? Choose, if he is wise. Mr., Richards, unfortunately, could not bring himself to choose between the welfare officer hero's professional and his private life, and consequently skipped disconcertingly from on to another without really doing justice to either. This is the sort of difficulty which is likely to arrive in adapting any novel longer than 20,000-40,000 word conte length, and the mind boggles at what would happen where the series to embark on J.R. Priestley in his expansive early phase, or any of the heftier current Americans. At any rate, it is clear that they are batting on a far from easy wicket, and the main wonder, all things considered, is that they have done so well so soon.

[The Listener 16/07/64]

Television

of the month

Television

of the month

Drama

BY JOHN RUSSELL TAYLOR

LAST MONTH LAST MONTH I deliberately left over one of the regular drama series, 'Story Parade', on the assumption, justified as it turned out, that it would be holding the fort virtually unaided for live - well, anyway, taped - drama during this month just past. With 'First Night', and 'Festival' gone, and 'Theatre 625' between bursts for three weeks, 'Story Parade' has been going it alone, with only a collection of repeats of the worst plays of the last year - exception made for Alun Owen's The Strain - as a little doubtful company. Consequently 'Story Parade', has had to stand up to rather more intense critical scrutiny than would normally be the case; and I think that, all things considered, it has been standing up quite well.

What are the things that have to be considered? Well, to begin with, that the series is meant, I take it, as very much a bread-and-butter sort of series, mainly popular in its appeal. This means, I hasten to add, not that critical standards will be lower, but that in many respects they will be higher; if a programme is breaking difficult new ground, either technically or in its subject matter, if its aims are ambitious enough, we shall probably be ready to make a few allowances for its shortcomings, but if its aim is primarily to entertain as many people as possible, we are unlikely to listen very patiently to excuses if it fails to do so. Art you can usually muddle along with somehow, but polished entertainment needs time, trouble, and money spent: Brecht's Galileo, for instance, looked very pretty with all the lavish production values 'Festival', gave it, but a lot would have emerged - in some respects, perhaps, even more - without them; on the other hand, take away the production values from the average successful thriller and what have you left?

So, judging 'Story Parade' as popular entertainment, we are in many respects judging it by the most exacting standards, and this should be borne in mind when it is necessary to say, as it quite often has been, that it fails. Where the series has failed the trouble may be diagnosed as coming in almost equal proportions from faulty choice of material and from faulty execution. Sometimes the choice of novel for adaptation (all the programmes are based on novels or short stories published in about the last thirty years) has been totally inexplicable from the finished result. Whatever, for instance, did the original novel of The Harp in the South (July 10) have to make the programme's devisers think it would dramatize satisfactorily? All that came over in the play Bruce Stewart made of it was a desperate collection of every cliché in the slum-drama book, with everybody always having babies or miscarriages, being raped or run over, drinking, celebrating winning a lottery (a mistake, of course), or having warm, human, extravagantly characterful clashes with the parish priest. The ensemble had a certain morbid fascination, being as richly grotesque an exhibition as we have been offered for some time, but entertainment one could hardly call it.

More often, though, the choice of material has been reasonable enough, but something has gone wrong along the way. I think, for instance, that it was probably a bit risky picking anything as slight and nuancé as the short stories adapted by Hugh Leonard for A Triple Irish (June 26), though Mr Leonard seemed to have done a capable job of adaptation and the result might have been rather charming. But here my point about the high standards required for successful light entertainment really applied with full force: Edgar Wreford's direction was one of the worst I have ever seen on television, lacking in pace, timing, flair, humour, a sense of effective pictorial composition, everything. And without a high gloss this sort of material just collapses, for if it isn't efficient entertainment it isn't anything. (This occasion was particularly irritating, incidentally, since BBC-2's 'real alternative' meant only that an hour of comedy drama on the second channel covered entirely a fifty-minute excerpt from what promised to be a piece of really efficient comic entertainment, Thora Hird in What a Joy Ride straight from the Grand Theatre, Blackpool; a planning, achievement now surpassed by the new Friday-night arrangement which makes 'The Defenders' clash with 'Arrest and Trial'!)

The rest of the recent programmes in the series have been more betwixt and between. John Wain's A Travelling Woman (July 3), neatly adapted by Jeremy Paul, made an agreeable change; though I thought its 'sophistication' a little strenuous and self-conscious to be altogether convincing, it was a reasonable stab at the Severed Head type of elaborate sexual shuffle, and was marred only by a few bits of over-production from David Bellamy: the speeded-up action for the journeys was all right once or even twice, but repeated ad nauseum practically every time anyone went anywhere it soon became a rather tiresome mannerism. Shadow of Guilt (June 19) was an innocuous thriller, quite well done in its way. But the best of all the series since the very first was Terry Nation's adaptation of Isaac Asimov's Caves of Steel (June 5), a fascinating mixture of science fiction and whodunit which worked remarkably well, despite a slightly specious, dragged-in attempt to suggest a parallel between the characters' attitude to robots and ours to racial minorities, simply on the level of mechanical excitement and visual invention. One would guess, judging from the sets, costumes, and miscellaneous gadgetry, that this was one of the series' most expensive productions, but if so it was worth every penny; and it seems, after all, that when money has to be spent, wooing the mass audience is the way of spending it which can be most readily judged by results.

Return to Caves of Steel review

Return to Star Begotten #21 Listing

| 25/05/99 | First Virgin Net upload |

| 06/06/99 | Minor corrections |

| 22/10/17 | Hosting transfer & amendments |

| 30/12/23 | Corrections |